Ar. Phillip Chang: The Architect’s Architect

Pioneer Architects in Sarawak

As part of BAJ’s Pioneer Architects in Sarawak series, this article continues our interviews with architects who shaped practice in Sarawak during the 1960s and 1970s.

The following excerpt is extracted and condensed from an interview by Megan Chalmers with the late Ar. Phillip Chang (1952-2023) was done in 2011.

MC: Tell us about your childhood, schooling, and hobbies.

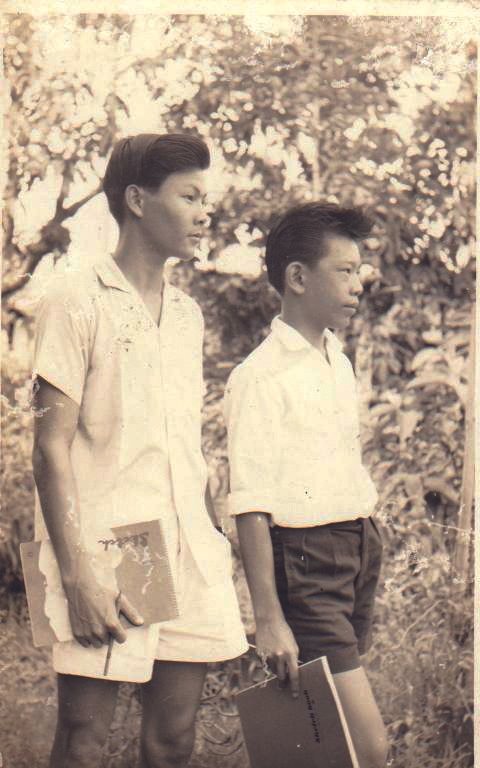

PC: I was born in Singapore in 1952 and moved to Kuching at a young age. I attended St. Thomas’s School from Primary One in 1957 right through to Upper Six in 1969. Like most schoolboys then, I had many hobbies—stamp collecting, reading, swimming, badminton and hockey. I also developed a strong interest in chess and eventually represented my school team at Sydney Boys’ High where I matriculated in 1970.

MC: When did you know you wanted to be an architect?

PC: I was always good at art and won several art competitions in school, so architecture naturally became my first choice. Initially, I was offered Economics and Commerce at the Australian National University, but Canberra didn’t appeal to me—it was far too cold. Two weeks later, I was offered a place at the University of Sydney to study Architecture, which at that time was one of the leading schools in the region.

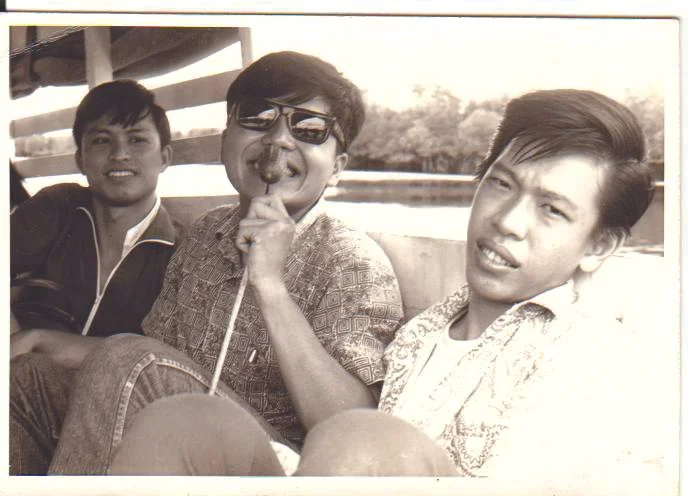

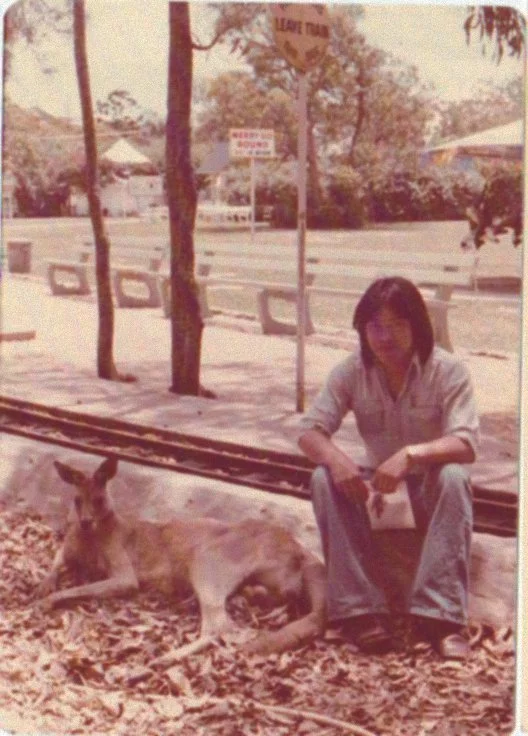

MC: What did you gain from your years in Australia?

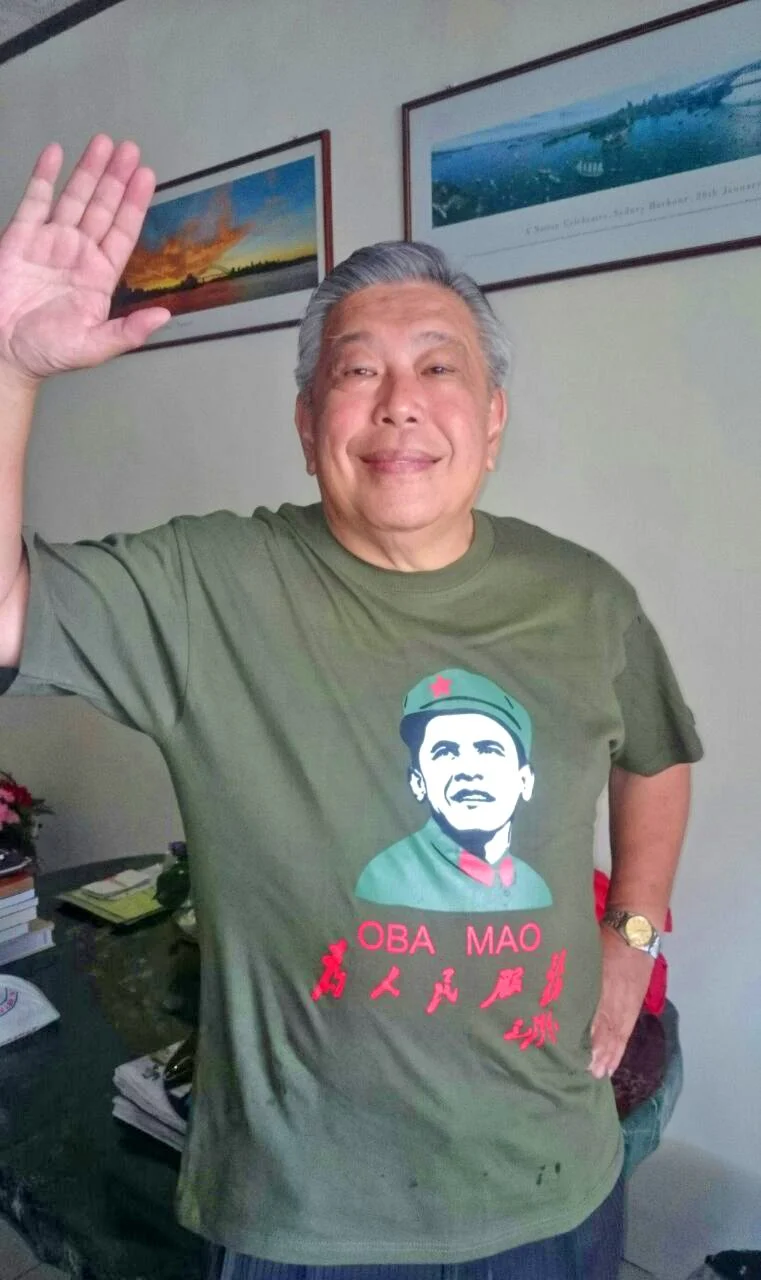

PC: Australia had a profound influence on me, both personally and professionally. Sydney University in the 1970s was a very politically active place. There were strong movements against the Vietnam War and for Aboriginal land rights. I became deeply involved in student organisations, particularly those with socialist leanings, and even helped campaign for the Labor Party.

I spent about ten years in Australia, studying and working. I worked at Planning Workshop Pty. Ltd., a master planning and architectural firm led by Darrel Conybeare, Bill Morrison and Peter Armstrong. Later, I joined Granada Homes, where I spent a year working directly on construction sites as a builder. That experience helped me understand the realities of building and site management, and it grounded my architectural thinking in practical construction knowledge.

MC: You studied under some influential architects and artists. Who left the strongest impression on you?

PC: Two lecturers stand out—Marr Grounds, the son of renowned architect Roy Grounds, and Professor Peter Johnson, who was then Dean of the School of Architecture and a partner in McConnel, Smith & Johnson. They shaped the way I thought about architecture and the profession.

I also took an art elective taught by Lloyd Rees, who was already in his eighties at the time. He was a giant in the Australian art world and still teaching, still telling stories about life and creativity. For a young student from Sarawak, that was incredibly inspiring.

MC: You returned to Sarawak and joined JKR. What was the architectural scene like then?

PC: At that time, architects were required to work in JKR before being allowed to sit for the PAM-LAM Part 3 examinations. Architects were also not held in particularly high regard compared to engineers. In fact, the Building Branch of JKR was once headed by an engineer, which tells you a lot about the hierarchy then.

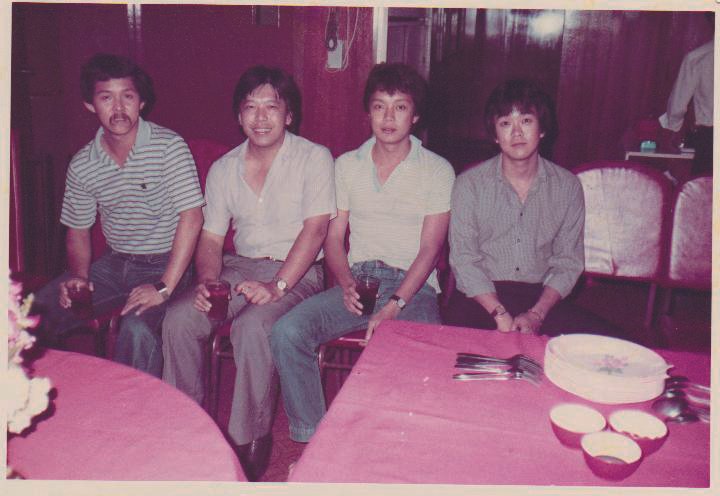

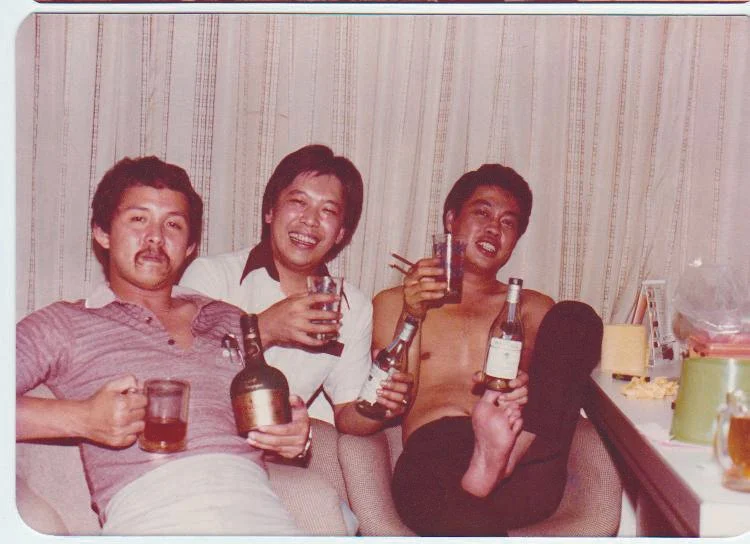

That said, I was fortunate to work with an excellent group of colleagues—Johnny Sim, Vincent Jong, Sim Eng Miang, Sim Teck Hian, Chin Kim Yu and others. Later, people like Simon Woon, Chew Chung Yee, Jon Ngui, Roland Tan and Stanley Chai joined us. We reorganised the Building Branch to function more like a team, and the camaraderie among architects was strong. That sense of unity helped many of us when we later moved into private practice. I feel that this collective spirit is something younger practitioners today are missing.

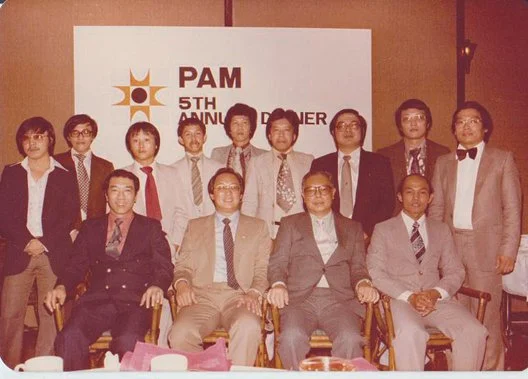

MC: You were also involved in reforming PAM Sarawak Chapter.

PC: Yes, in the mid-1980s, a group of us worked to reinvent PAM Sarawak Chapter and raise its profile. We encouraged the older leadership to step aside and persuaded John Lau to take on the chairmanship to improve PAM’s image. We also lobbied PAM headquarters in Kuala Lumpur to remove the compulsory JKR service requirement before sitting for professional exams. In hindsight, that change may not have been entirely positive, but at the time JKR could not cope with the number of returning graduates.

MC: In 1982, you left JKR to form United Consultants. Why?

PC: Quite frankly, I realised I would go mad if I stayed in JKR. It was time to move on. I resigned in 1982 and joined Wee Han Wen and several engineers to set up United Consultants, a multidisciplinary practice. We opened our first branch in Miri and later expanded to Kuching.

Multidisciplinary firms were quite common then, and they made sense. When building projects slowed down, infrastructure work could sustain the firm, and vice versa. Clients also benefited from cost savings when architectural and engineering services were integrated. Over time, we grew to about 40 staff and worked on projects throughout Sarawak.

MC: Which projects stand out most in your career?

PC: The Kuching Waterfront would be at the top of the list. Completed in 1993, it was a collaboration with Conybeare Morrison and Partners from Sydney. The project involved about one kilometre of riverfront promenade, parks, and public facilities. We also adapted several historic buildings for reuse—the Square Tower became an interactive museum on Sarawak, the Sarawak Steamship Building was turned into a restaurant and craft centre, and the former Chinese Court House became the Chinese History Museum.

Old warehouses were removed to open up the riverscape, and artworks along the waterfront reflected Sarawak’s diverse ethnic communities. It was a meaningful project because it combined urban design, heritage conservation and cultural expression.

Curtin University Malaysia in Miri was another major achievement—our first university project—done in collaboration with JCY Architects from Perth.

Friendship Park in Jalan Song was also memorable. The local council had no budget for the Malaysian elements, while the Municipality of Kunming in China contributed the Chinese components. They designed and built the entrance arch, pavilions and a bronze statue of Admiral Zheng He, bringing in artisans from China. Watching them carve stone and paint intricate patterns on site was truly remarkable.

MC: You spent 17 years as a councillor with MBKS. What motivated you?

PC: I joined the council because I wanted to change the system from within. Too many policies affecting architecture and building were being set by people with little understanding of our profession. Instead of complaining, I felt it was more meaningful to participate directly and provide an architect’s perspective at council meetings.

As architects, we have a responsibility to the community because our work shapes the built environment. Being in the council allowed me to act as a bridge between architects and local authorities.

MC: You also taught at Lim Kok Wing Institute of Creative Technology. How was that experience?

PC: I was approached by Dato’ Prof. W.Y. Chin to teach Architecture Drawing to senior students. I taught there for three years and found it extremely fulfilling. In fact, I wish I had started teaching earlier. Unfortunately, increasing work and travel commitments meant I had to step away.

MC: As a senior practitioner, what advice would you give young architects?

PC: I strongly encourage young architects to work overseas, either as consultants or builders, before returning to Sarawak. Overseas exposure teaches discipline, work ethics and how things should be done properly. I feel that a strong work ethic is missing among many young architects today.

I am also concerned that many graduates do not want to sit for the LAM Part 3 examination. Choosing to remain salaried without professional responsibility is unhealthy for the profession. Architects must be willing to take responsibility for “signing the drawings.”

Finally, architects must remember their role as leaders—the captains of the ship. Too many rely excessively on sub-consultants, especially quantity surveyors. Architects are paid higher fees because we are expected to understand many disciplines. Once we lose that leadership role, we lose respect, and ultimately, we lose relevance.

MC: Have you thought about retirement?

PC: I have thought about it, but we still have active projects, including some overseas. The future remains exciting. If I were to retire, I would return to painting and creative arts—going full circle back to where it all began.

End of interview.

interviewed by Megan Chalmers

EPILOGUE

By Wee Hii Min

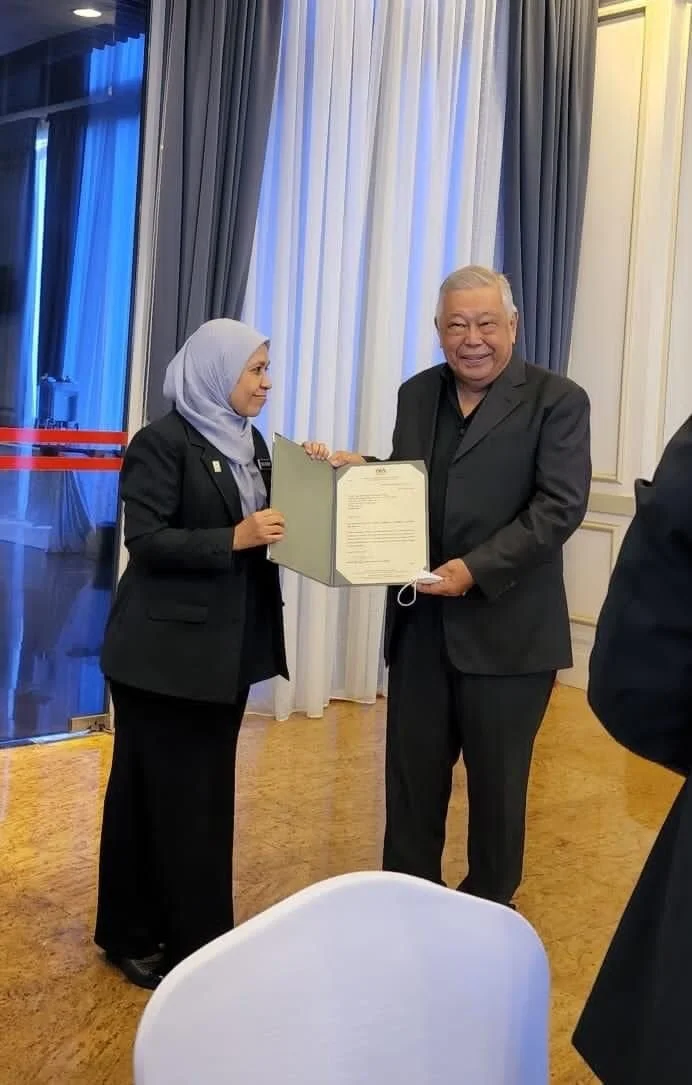

Philip did not retire. He continued to work on his projects and worked tirelessly in his capacities at PAM Sarawak Chapter and Lembaga Akitek Malaysia. In 2019, he set up CATUS; a new practice with Stephen Liew, Law Kim Chui and Wong Kiong, he travelled more, bought more books for his new house and presumably planned greater adventures.

And then on the 29th of April 2023 after a short illness, Philip passed away. He was only 71.

It always comes as a surprise when tall timber falls. Especially in our profession where the Almighty seem to bless us with old age. With his passing, Sarawak lost one of her pioneer architects - friends and colleagues remember him as tireless advocate for the advancement of our profession, as a generous mentor and a true professional.

For me, he was an architect’s architect – someone who read broadly; proficient in many subjects and able to discuss or debate any of them with anyone who cares to take up the topic, with equal measures of wit and wisdom. I am fortunate to have an insight into Philip’s appetite for books, as I ‘inherited’ his library after his passing – approximately 3000 books and magazines on architecture, politics, memoirs, books about local culture and history, about flora and fauna, there were novels and scientific journals, how-to guides to water-colour, photography and Photo-shop. And judging from the number of recent purchases still sealed in plastic and the numerous self-made bookmarks (name cards, strips of greeting cards, ringgit notes) found in between many books, it appears that Philip planned to find time to finish reading his library. It saddens me that he was unable to, because the man I knew (briefly) likes to finish what he starts. Philip leaves behind his wife, Tan Moi Moi and his children, Byron, Dwayne and Melissa.

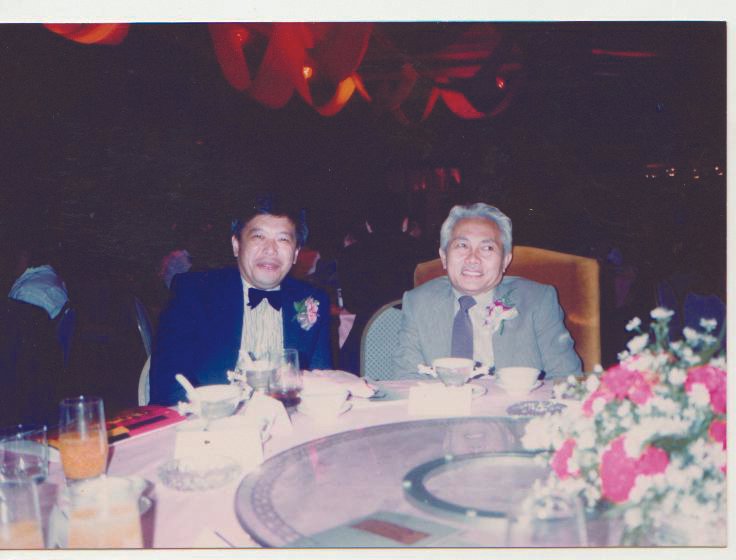

PHOTO GALLERY